When filmmaker Patrick O’Connor first met Amber Olsen in 2017, connected by a mutual friend, he thought he would be making a simple GoFundMe video. But the meeting, and the video, was anything but. Amber told Patrick that her younger daughter Willow, three years old at the time, was battling an ultra-rare lysosomal storage disorder called Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency (MSD).

“At the time of her diagnosis,” Amber explains now, “there were less than 50 known cases in the world. I read the Wikipedia page which said there was no treatment and no cure, and children with MSD usually didn’t live past five years old.”

During their meeting, Amber explained to Patrick that finding a treatment for MSD relied on advancing research into gene therapy. But developing and testing the treatment would cost several million dollars.

Patrick shares, “Amber had met another mother on Facebook whose daughter had a similar condition. The woman had raised money to buy a herd of sheep for a toxicology study. Amber told me she was going to do the same.”

But the idea flummoxed Patrick. Why would Amber have to buy sheep? Why weren’t research institutions, or the National Institutes of Health (NIH), leading the charge?

“I wouldn’t have thought anything else in a rational world,” he recalls. “But then it hit me. The push for change, the research, the fundraising, it all falls on the moms. That’s what made me think there was a larger story here about the drug development space in rare disease and the toll it takes on parents.”

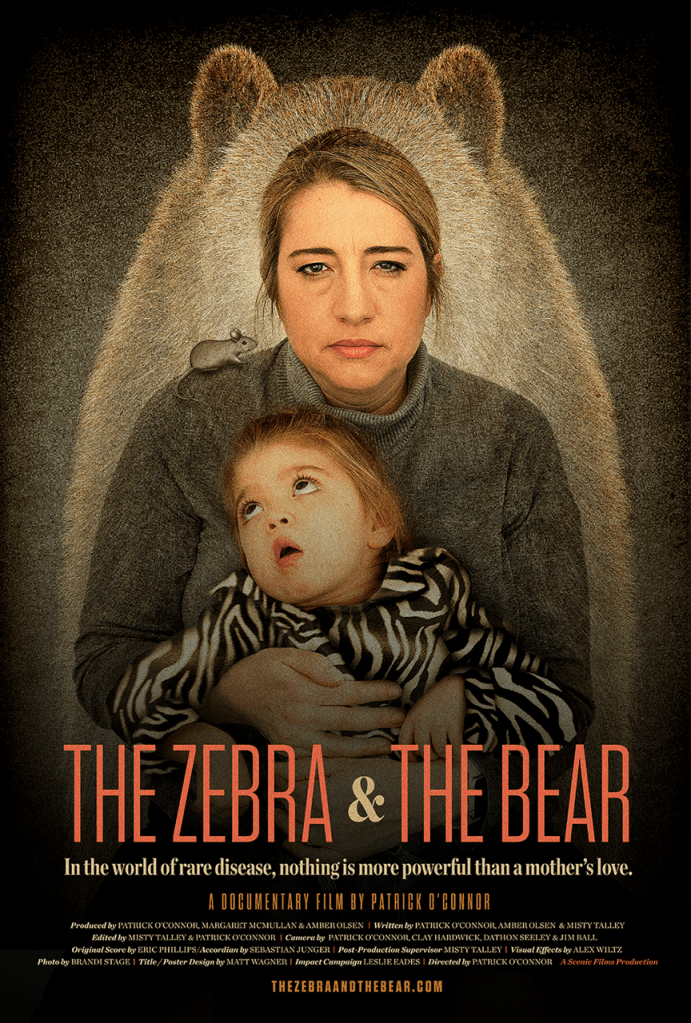

His realization became the foundation of The Zebra & The Bear, a documentary that followed Amber and her family for seven years as they raised millions of dollars, navigated pharmaceutical partnerships, monitored mouse studies, and fought to get a gene therapy to clinical trials. The documentary captures the reality of parents of children with rare diseases and the struggles of trying to maintain a job, a family, advocacy and research efforts—all while trying to keep your child alive.

“This is not a hero story,” Amber says. “This is the story of thousands of families and what they go through.”

Before the Diagnosis

Willow came into the world as the third of Amber and her husband Tom’s children, following behind Kylee and Jenna. In the documentary, Amber describes Willow as vivacious, bright, and joyful—a girl who truly brought light to whatever room she was in. By the time she was two years old, Willow was walking and running.

But Amber had a few concerns. Willow had always been small in stature, and her development lagged behind other children her age. She did not speak and would put random objects, like the couch cushion, in her mouth constantly, driven by a sensory craving.

Early medical appointments yielded few answers. Doctors suggested that Willow might have a hearing issue, or that removing her adenoids might yield improvement. But it wasn’t until the family met a pediatric neurologist, Dr. Lee, that answers began to emerge. Dr. Lee noted that Willow was developmentally regressing, or losing skills.

A genetic test found that Willow was a carrier for multiple sulfatase deficiency. But was that causing her symptoms? Another genetic test, to determine if she actually had the disorder, took two months to come back. Two months of not knowing.

But the second test confirmed what the family had been dreading. On May 9, 2016, it became official. Willow had MSD.

“Devastating is not the right word,” she says in The Zebra & The Bear. “Every moment was now a terrible ticking clock, something we were racing against.”

What is Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency?

Multiple sulfatase deficiency is a rare genetic lysosomal storage disorder caused by SUMF1 gene mutations. Our cells contain structures called lysosomes that filter out waste by breaking down and recycling cellular debris. 17 sulfatase enzymes help break down some of these molecules. Without this, molecules containing sulfatase experience build-up and then cell death. In MSD, cell death especially affects the brain, skin, and skeleton.

According to the United MSD Foundation, which Amber established in 2016, three subtypes of MSD exist: neonatal (the most severe form present in utero or at birth), late-infantile (the most common form with no signs at birth, but later regression), or juvenile (the rarest form, where symptoms do not appear until mid to late childhood).

Early features of MSD may include:

- Difficulty balancing

- Developmental delays and/or failure to meet milestones

- Dry skin across the entire body

- Recurrent ear and/or sinus infections

- Seizures

- Increased muscle tone

- Difficulty eating or swallowing (dysphagia)

- Coarse facial features

- Poor sleep

- An enlarged liver or spleen

However, each child with MSD is different and the disease may manifest in different ways.

There are no treatments or cures for MSD. In the film, Dr. Brian Kirmse, the pediatric geneticist at the University of Mississippi, explains, “It’s a progressive and severe disorder. Most patients with MSD die before their 10th birthday.” Many children with MSD experience increasingly severe and frequent respiratory infections that can lead to pneumonia, which may be fatal.

Moving Towards Change

As Patrick began documenting the family for The Zebra & The Bear, he saw the multitude of interventions Amber used for her daughter. Willow used a percussion vest, or a device which shook her body for 20 minutes twice a day to release secretions in her lungs and body. Most people clear these naturally through regular movement, but Willow wasn’t mobile enough for that to happen on her own.

The family also had a cough assist machine and a nebulizer, and at one point gave Willow 0.5 grams of genistein three times daily. “It could potentially take the trash out of the cells,” Amber shares.

Throughout this process, Amber had also started reaching out to doctors, researchers, anybody who she thought might listen. She found a glimmer of hope in Texas when Dr. Steven Gray, the co-director of the UT Southwestern Gene Therapy Program and a renowned leader in AAV gene therapy vectors for rare and ultra-rare conditions, agreed to meet.

Dr. Gray had recently developed a gene therapy for giant axonal neuropathy (GAN) which replaced the mutated gene with a healthy one, giving the body’s cells the right instructions to produce functioning enzymes. Amber wanted to understand whether a similar approach might work for MSD.

The process would take time, Dr. Gray explained. Then, gently, he mentioned that the treatment might not help Willow. In the documentary, Amber begins to cry before telling Dr. Gray, “I know. We just need to do this for the next group of kids. This is Willow’s way of leaving a legacy.”

So Dr. Gray told Amber the next steps. The Zebra & The Bear captures the eight steps to a gene therapy for MSD:

- Create a nonprofit and fundraise $3-5 million.

- Contract with the Jackson Laboratory to breed mice engineered to have MSD.

- Contract with a research scientist to create the viral vector with the gene to be injected into the mice.

- Inject the mice.

- If the mice get better, submit the results to the FDA and request a pre-IND meeting to move to a toxicology study on a larger animal.

- Find a pharmaceutical manufacturer that can make enough for the toxicology study and eventual clinical trial.

- Identify a research hospital that could manage the clinical trial.

- Select children to be treated. Monitor results. Pray that it works.

“It was completely overwhelming,” Amber tells me. “I had a dying child and also had to learn how to create a foundation, run it, and fundraise huge numbers. We’ve all done bake sales and Girl Scout cookies, but the entire concept of raising millions is very difficult. Big universities have a hard time collecting that amount of money. Now moms and dads have to do that.”

“It’s unethical and unfair that the parents have to bear this,” Patrick adds. “The main thing that struck me was this constant feeling that Amber and her family should not have to do this. I understand meeting with scientists and the research. But watching her, her family, her husband basically beg people for money was very difficult.”

Amber started to fundraise anyway. What choice did she have?

Refusing to Stop

Amber threw herself into intense fundraising. She created videos, gave presentations, ran fundraising events, met with potential donors—anything to advance awareness and get the research to where it needed to be.

“I spent every day for seven years trying to raise that money,” she says. Thinking about her efforts is bittersweet. On one hand, it was Amber’s tireless work that contributed to significant change for the MSD community that can help children moving forward. On the other, Amber was on calls with scientists, at fundraising events, in meetings. She was fighting to save Willow’s life, but doing so also meant missing some of it.

By two years in, Amber had raised enough money to begin mouse studies. As Amber explains, the first knockout mouse model of MSD had already been developed in Italy in 2008. “Since we knew it was a single gene disorder and knew the source, we had the mice sent to Jackson Laboratory to be bred,” she says. “UT Southwestern created the gene therapy and Jackson Labs injected the mice with the medicine. It was very efficient to get that done.”

Amber joined monthly calls to review the results, tracking whether the mice were surviving, declining, or showing any changes. Early on, it was clear that the knockout mice typically died within days, but the treated mice survived. “The efficacy was so amazing,” Amber says in the documentary, “that it was time to start preparing for clinical trials.”

“The science is amazing and so interesting to see up close,” Patrick adds.

With proof of concept from the mouse studies, Amber needed to move to the next phase: toxicology studies, manufacturing, and preparing for clinical trials. But once again, the financial aspect became challenging. Taking the studies one step at a time would take too long, and Willow didn’t have years to spare. It’s best to fund the toxicology and manufacturing at the same time with the same manufacturer. “So we kept waiting,” she says.

Amber also knew that, unfortunately, rare disease communities sometimes find themselves competing for pharmaceutical attention and funding. Every patient foundation is fighting for the same limited pool of donors and grants. “The way drugs get developed is based on a financial statement and how profitable it will be to a company,” Amber says. “Not on whether the medicine works.”

But, at the same time, she needed to make MSD an attractive target for potential pharmaceutical partners. So she began identifying more patients, building a database of everyone diagnosed with MSD worldwide—“the numbers are small, less than 200 known, so we tried to reach out to everyone,” Amber says—and establishing a biobank to collect biological samples that could be used to identify disease biomarkers. She pushed scientists for plans for supportive studies that would provide additional data on how MSD progresses and how treatments might be monitored. “The farther we could get along, we were de-risking it. We wanted pharmaceutical companies to look at us, to pick us,” she says.

The Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium

As Amber continued her work towards advancing research, Willow’s condition began to deteriorate. Her respiratory infections became more frequent and severe, even leading to pneumonia. At one point, doctors even recommended a tracheostomy. As devastating as it was, seeing her daughter only solidified Amber’s deep desire to make a change.

Then came a breakthrough through the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS)’s Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium. The Consortium, part of the Accelerating Medicines Partnership, sought to create gene therapy resources to streamline gene therapy development and reduce costs. The program planned to award grants for five different diseases, covering manufacturing, toxicology studies, and clinical trials. The MSD clinicians and scientists applied immediately—and MSD was selected as one of the first diseases the Consortium would support.

“PJ Brooks, who leads the Consortium, said one of the main factors to include MSD in the initial group of diseases was all the work that Amber and other parent foundations had pushed to get funded, so they had all the supporting data to point in the right direction,” Patrick says. “This de-risked it for the NIH because they already knew that it looked like it would work.”

He pauses, then adds, “But we want people to understand—this is not the model anyone should want. The idea that the mom has to pay for all this groundwork just to make it attractive enough for institutions to consider is unreasonable.”

Still, Amber was excited to have been chosen. The Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium will pay for manufacturing the AAV9 gene therapy and for treating a small group of children in a clinical trial. The trial will hopefully begin in 2026.

To Amber, this milestone is mind-blowing. “I built a story in my head of being there on the sidelines when the first child goes in to get treated,” she says. “Just this incredible moment of a family who has something that is going to stop this disease and what that means for the child. These gene therapies are really changing the trajectory.”

Too Late for One, Hope for Others

Sadly, Willow’s disease continued to progress. Many of her brain cells had died and the damage was irreversible. Even if the gene therapy could stop MSD from progressing further, it couldn’t bring back what was already lost. By 2023, Willow’s cognitive decline became clear. She no longer responded to her name or recognized Amber when she walked into the room.

The clinical trial would likely not be effective for Willow. As much as it hurt, Amber understood. She had always known that her fight might not save Willow. But if the work could save other children, if it could spare other families this nightmare, then it wasn’t for nothing.

Willow passed away at age eleven in October 2024, surrounded by her loved ones. But her legacy lives on. “She never got to tell us what she wanted to be, but she just might change the world,” Amber says.

The Film as a Testimony to the Realities of Rare Diseases

Over his seven years of filming, Patrick gained a valuable and thought-provoking look into what rare disease families across the country, and the world, face each and every day. He documented fundraising events, scientific meetings, trips to research institutions. The soaring highs and the crushing lows as Willow became sicker and her parents became more desperate. And initially, he wasn’t sure how it would be received by other rare disease advocacy groups during screening.

“I was afraid they would think, ‘Why am I watching this? I live this.’ But what I realized was that this film offers relief. Parents who are in Amber and Tom’s situation see that they aren’t alone. There’s a community of people going through the same thing, or a version of it, and that’s valuable,” Patrick shares.

The film validated their experiences, their exhaustion, their recognition that the system is fundamentally broken and needs to be fixed. Amber, watching the documentary back, felt that same sense of validation, saying, “It validates how crazy this is. Even doctors and nurses would tell me, ‘Wow, I didn’t realize what you went through.’”

Looking to the Future

The gene therapy for MSD is currently in the manufacturing stage, but, as shared earlier, should move forward in 2026.

“MSD will probably be the first disease being treated in the entire Consortium,” Patrick shares. “The work that Amber has done, if this gene therapy works the way everyone thinks it is going to, is going to change the future. If it works, an infinite number of generations of children will not suffer from this disease. That’s enormous.”

The implications of this treatment also extend far beyond MSD. Amber points out how the gene therapy, which uses a viral vector called AAV9, can cross the blood-brain barrier and deliver treatment directly to brain cells.

“They’re going to use us not only as an example of how to get through clinical trials in a meaningful amount of time, but as a playbook for other diseases,” she shares. “This approach could be potentially useful for neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease.”

However, beyond the clinical trial, both Amber and Patrick believe that more needs to be done to improve rare disease research and treatment development. Currently, only 5% of rare diseases have an FDA-approved treatment. “The rare disease space is what a mom recently described to me as the wild west,” Amber says. Parents are leading the charge and driving scientific research. “But it’s not efficient for us all to be doing it this way,” Amber says. “We could do rare disease drug development more efficiently if we thought about it on a bigger scale.”

She envisions something like St. Jude’s, but for rare disease—a centralized institution with coordinated resources, research, and funding. If a parent received a rare disease diagnosis, they could call a hotline where experts would help them figure out the next steps. More focus would be given to developing treatments that could potentially work, or be tailored, for several rare conditions.

Patrick notes that Dr. Sean Ekins had attempted to develop a similar institution, but the funding wasn’t yet possible. “It makes so much sense for parents and patients, but it’s a bridge too far right now,” Patrick says.

Right now, the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium remains a step in the right direction. And parents like Amber continue to innovate, continue to advocate, continue to push. But parents cannot and should not bear the entire burden of drug development. One program isn’t enough.

“If this is the only way drugs are going to be developed for rare diseases, we’re never going to get there,” Amber says.

Watch The Zebra and the Bear on Apple TV, Amazon, Google Play, Vimeo, or YouTube Movies & TV to get a better look at Amber’s story and to better understand what rare families are facing.

If your child has been diagnosed with multiple sulfatase deficiency, or you’d like to learn more about MSD, connect with the United MSD Foundation on Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube. Every contribution helps move treatments closer to the children who need them.

Leave a comment