In a small town nestled among South Dakota’s farmlands, everything changed for Jordan Kruse and her family. The change didn’t come in a dramatic, cinematic way; it came quietly, in the hushed discomfort of a newborn who simply showed no more interest in nursing.

Pruitt, Jordan’s third child, had come home from the hospital as a seemingly healthy baby. His delivery was smooth and uneventful — a stark contrast to Jordan’s previous pregnancy, where she had hemorrhaged while giving birth — and the newborn screening panel came back clear.

After a difficult pregnancy marked by Jordan’s gestational diabetes and Pruitt’s dilated kidney, which the family assumed they’d have to medicate him for, Jordan allowed herself to believe that they were finally in the clear.

Unfortunately, that only lasted around 48 hours.

By the time Pruitt began making a low, grunting noise and refusing both nursing and a bottle, Jordan’s instincts had kicked into hyperdrive. She and her husband, both teachers, immediately brought Pruitt back to the hospital.

“He had a sepsis workup,” Jordan tells me, “but every test came back as normal. The doctors came to realize that there was no bacterial infection like they had suspected.”

The next two days passed in a blur of concern or confusion. Then, finally, a proposal: after a consultation with the genetics team, an ammonia lab was ordered for Pruitt. A healthy ammonia level in infants is 45±9 micromol/L. Pruitt’s value was over 1,000 micromol/L!

But now the Kruse family had an answer to what was going on with Pruitt: ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTC deficiency), a rare urea cycle disorder that disrupts the body’s ability to rid itself of ammonia.

Hyperammonemia, or the excess buildup of ammonia, can cause serious consequences including neurological damage, cognitive impairment, failure to thrive, organ failure, and coma. For Pruitt, the neurological impact had already begun. “If someone had thought to run the panel earlier, things would have been much different,” says Jordan.

Suddenly, the Kruse family found themselves at the center of a complex and high-stakes medical fight.

Understanding OTC Deficiency

Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency is a rare, X-linked genetic disorder that affects approximately 1 in every 8,200 live births in the United States. Because the OTC gene sits on the X chromosome, this condition appears more frequently (and also more severely) in males.

However, a study from the Urea Cycles Disorder Consortium found that the risk of developing hyperammonemia in “asymptomatic” female carriers could be as high as 15% — and “~38% of [asymptomatic] and 33% of [once asymptomatic but not symptomatic] subjects suffered from mild to severe neuropsychiatric conditions such as mood disorder and sleep problems.”

But OTC deficiency is currently not included on any state’s newborn screening panel, says Tresa Warner, the Executive Director of the National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation (NUCDF) and a mother to a daughter with OTC deficiency.

“Today, one of the biggest struggles for our families is getting an early diagnosis,” Tresa explains. “So many families get a diagnosis too late or struggle for months. Right now, there are six urea cycle disorders. OTC deficiency, the most common urea cycle disorder, is not included on all newborn screening panels due to lack of an adequate test. This lets children fall through the cracks. Even with newborn screening, depending on the day a baby is born and how the results are batched, even a day delay can make a difference. One of our goals is expanded newborn screening to ensure all patients are diagnosed in a timely manner.”

The lack of newborn screening and standardized care means that parents like Jordan and her husband are left to navigate OTC deficiency’s rapid and life-threatening onset with no warning and often little guidance. The condition is also poorly understood in the medical field.

When Pruitt’s test came back for OTC deficiency, the hospital staff — although Jordan acknowledges “gave us what they could” — were also navigating uncharted territory. Pruitt was the first child with OTC deficiency that the hospital had ever seen.

“They were doing their best to find a formula that worked with him and our geneticist was reaching out to consult with other hospitals. We also received a pamphlet about urea cycle disorders, and the social worker gave us more info on NUCDF and the National Organization for Rare Disorders. But it was hard knowing nobody around us was facing similar challenges. Plus, dealing with postpartum and caring for my other children on top of this was overwhelming,” Jordan says.

Improving Future Care

As she reflects on her experience, Jordan believes that medical staff and physicians could do more to support families whose children have a rare condition. She explains, “When you’re in the hospital, it’s hard to know what life is going to look like outside of the hospital doors when you have to do all of these things that are new and scary. Knowing what I know now, I’m hoping they could provide more to families in terms of support. Even just providing a connection to other families, or having a touchpoint that we could go back and communicate with, would be incredible.”

But outside of psychological, emotional, and resource-oriented support, Jordan also stresses the importance of physician education. “Physicians are taught to look for the most common things while the rare conditions are overlooked and not considered,” Jordan says. “We really need to educate physicians and push for expanded newborn screening. That would be a gamechanger.”

Bringing Pruitt Home

After the diagnosis, the Kruse family found themselves managing the needs of a medically complex child. Their schedule ran with militaristic structure:

- 24/7 feedings through his NJ, then eventually GJ, tube

- Weekly doctor appointments and check-ins

- Four medications every four hours around the clock

- Gabapentin for neurostorming and Keppra for seizures

- Occupational therapy, physical therapy, and in-home nurses

But at the same time, Jordan says, “his schedule was always changing every time we got admitted to the hospital.”

Any deviation to the schedule risked destabilization. “The disease is so invisible. It’s hard to see the signs of high ammonia,” Jordan explains. “We lived in fear of when the next ball was going to drop. Even mild illnesses could trigger a crisis. We had to be very observant, paying attention to any cue he could give us. We also had an emergency care plan that we made sure all family members knew, just in case something happened. It affected our family dynamic, because our other sons Paxton and Prior sometimes had to wait while we prioritized Pruitt’s health. For families that face this, it isn’t an easy lifestyle.”

Siblings often find themselves in a unique position in rare disease families. Some siblings may find themselves feeling isolated or guilty that they add to the challenges their family is facing. But resources are available. In addition to Global Genes’ RARE Disease Siblings Resource Guide, Tresa shares that the NUCDF has emphasized sibling support as a key tenet of its advocacy work.

Despite it all, Jordan knows she would once again step up for Pruitt, saying, “You embrace it. It becomes your new normal and you become the rockstar you never thought you could be. You’re scared, but you have to tackle it. The care was a lot. But we would do it again in a heartbeat if it meant he was here.”

The Possibility of a Liver Transplant

There was talk of a liver transplant for Pruitt. OTC deficiency can be effectively cured by liver transplants, which can offer metabolic stability. But given Pruitt’s early neurological damage and the severity of his OTC deficiency, his care team advised waiting.

“They gave it to us straight,” Jordan says. “We asked what they would do if they were in our shoes, and they told us to see how he would progress. They also described it as trading one problem for another: it would fix his OTC issues but would never fix his health from a neurological standpoint.”

In the interim, Jordan frequently spoke with other OTC deficiency moms on Facebook, stating that the family support system and online support system were both huge in helping her navigate her fears.

“Seeing what some people dealt with gave me the hope that we could overcome these challenges too,” she shares, “but at the same time, not every story has a good outcome. Every family’s journey is unique based on their circumstances, dynamic, and interpretation of quality-of-life. It’s hard trying to balance that: we could be the family that survives and thrives, but we could also be the family that loses our child.”

As months passed and Pruitt grew older, the Kruse family noticed some delays — but they remained hopeful. Eventually, the decision was made to do a liver transplant.

Unfortunately, they never had the chance to get listed. While the family was waiting for insurance, Pruitt developed a minor illness that put him into a metabolic crisis. Pruitt passed away at six months old.

“And we’ll always live with the what-ifs,” Jordan says.

Navigating Grief

Grief is a lifelong journey and a near-constant rollercoaster of emotions. No parent believes that they will bury their children first.

“If it wasn’t for my other two children, I don’t know where I’d be,” Jordan tells me. “They keep me going. My husband is a rock. Still, I had this purpose when Pruitt was here — to focus on his care. To give 100% into his medical complexities. When that bond was stripped from me, it was hard. I went from going 100 miles per hour to now having all this time on my hands.”

Grief support groups have been helpful for Jordan, though she acknowledges that they can be heavy and difficult. But the benefit of grief support groups is that “it makes you feel like you’re not alone. Those feelings you’re facing — seeing other people getting through it gives you a sliver of hope that you can face it too.”

Jordan will never forget Pruitt. Despite his medical challenges and the battles he faced, he was easy-going and lovable. Jordan laughs as she explained that Pruitt “could give some good side-eye,” but adds that his cuddles were the best.

“God placed him in our lives for a reason,” she says, “and we know we’ll see him again one day. It’s just a matter of when. That’s what keeps me going.”

Pruitt changed his parents and siblings for the better during his six months on Earth. He was brave and resilient; he opened their eyes to seeing the world in a brand new way. “We learned to be more present, to slow down and cherish the moments we have with the people that matter,” Jordan reflects. “He taught us so many lessons. We were very blessed.”

The Brave Little One Foundation

In the weeks after Pruitt passed, Jordan found herself adrift. But what came next was born of grief, of urgency, and of an unshakable belief that other families shouldn’t have to walk the same path in the dark.

“I was heartbroken knowing that children and other families are often misdiagnosed or, in our case, not diagnosed quickly enough,” says Jordan. “I wanted to bring that awareness piece to people’s lives to prevent things like this from happening in other families. The journey can be isolating, scary, and lonely. You find yourself explaining what the disease is because medical professionals might not know. I don’t want Pruitt to be forgotten, so I turned pain into purpose.”

Jordan founded The Brave Little One Foundation as a way to honor Pruitt’s memory and address the gaps she and her family had lived through. The foundation offers support to families facing medical hardship, advocates for awareness of rare conditions like OTC deficiency, and provides adapted clothing through a project called Pruitt’s Closet, named for the difficulties she had finding accessible outfits for a baby with a GJ tube.

“The majority of his clothes weren’t accessible,” she said. “I didn’t have a lot of time so I made holes in them with iron-on patches. Clothes for kids with feeding tubes are ridiculously expensive, and I realized I probably wasn’t the only one who lacked access.” Community-donated clothing is now adapted and sewn to suit children with feeding tubes, offered at no cost to families.

The foundation will also fund two annual scholarships for graduating high school seniors in Lennox and host a yearly golf tournament, an event first organized by the community in Pruitt’s honor.

Every Friday, Jordan posts a fact about urea cycle disorders in an effort to keep education consistent, accessible, and visible. If you’d like to follow along, you can check The Brave Little One Foundation out on Facebook or Instagram, in addition to its website.

Think Rare, Act Fast

As Jordan looks to the future, the message she wants physicians to hear is simple despite the weight it carries: think rare and act fast.

“With urea cycle disorders, timing is so important when it comes to outcome,” she says. “I want doctors not to just assume everything is common. Think about the big picture. In Pruitt’s case specifically, ammonia testing could have changed a lot for him. It takes a little bit of time, it won’t hurt the baby, and there’s already tests being run. Ammonia testing can save lives – and it isn’t just the lives of the patients now, but awareness that can save generations.”

The campaign to expand ammonia testing — #CheckAmmonia — is currently being revived by the NUCDF and sponsored by Zevra Therapeutics. The importance is clear to Tresa, whose daughter was diagnosed with OTC deficiency in the 1990s. Today, her daughter is 27. At the time, she had contacted the NUCDF for help. Now she sits as their Executive Director.

“I decided that you need to have a seat at the table if you want the best outcomes for your child,” she shares.

To Tresa, the #CheckAmmonia campaign is so important because missing the signs of hyperammonemia can be deadly.

“An ammonia test isn’t usually in the toolbox for a pediatrician, ER physician, or general practitioner,” she says, “usually just for patients in advanced liver failure or cirrhosis. But with metabolic conditions, ammonia testing needs to be the first thing they think of. We’ve lost young adults over the last few years who present as though they were intoxicated. They’re treated for alcohol or drugs instead of checking ammonia, which can cause irreversible damage. We want doctors to know what the signs and symptoms look like. A $30 test can save lives.”

NUCDF Efforts

Outside of the campaign, the NUCDF does a significant amount to support the urea cycle disorder community, including (but not limited to):

- Providing a UCD guide for new families to explain urea cycle disorders

- Caregiver support to tackle burnout and stress —

- “As a parent,” Tresa says, “our focus is making sure that our child is taken care of no matter what. Caring for someone with a urea cycle disorder can be incredibly stressful. Our goal is to provide resources to help caregivers. A healthy, happy caregiver can take care of a patient.”

- Providing resources for teachers and schools to better understand urea cycle disorders and UCD management

- Partnering with nurse practitioners to discuss filling the gaps in education “even around smaller things that are widely known but not necessarily known by new families, like: you can’t use steroids”

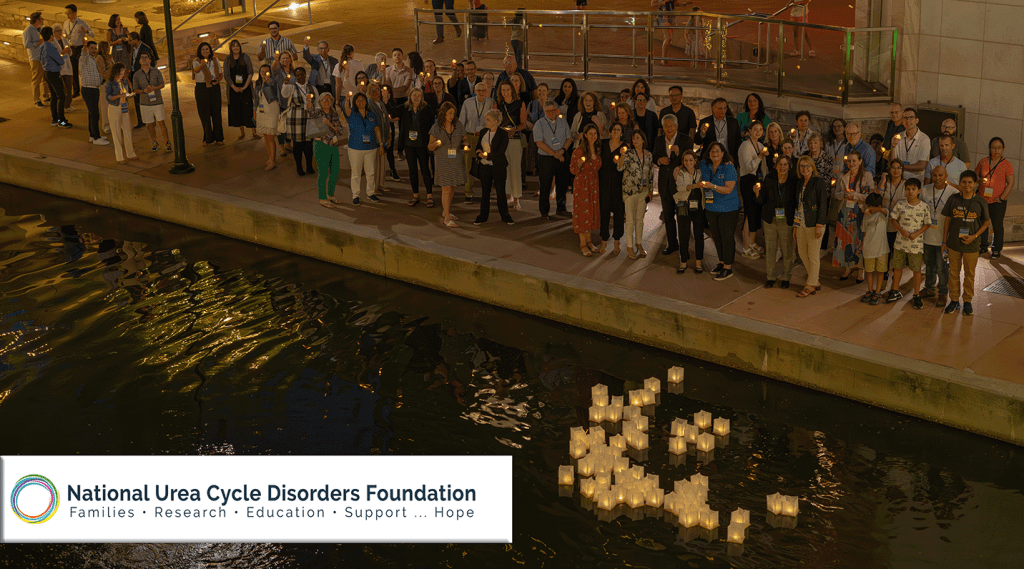

- Running 1-2 family conferences per year, as well as fundraisers like the Mythical Ball

- Incorporating parents into advocacy through the patient advocacy group

- Advocating for expanded newborn screening panels

- Pursuing research

Specifically, Tresa emphasizes how foundational patient-driven research has become. The foundation works closely with 14 centers of excellence nationwide, along with its research partner the Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium.

“This lets us enroll patients into the largest longitudinal study with the NIH. Our goal is to get families into that study so they have access to a center of excellence, especially if you’re in a pocket of the country that lacks access to care,” says Tresa. “

One of the organization’s most pressing goals is advocating for all UCDs to be included in expanded newborn screening panels: a fight made harder by the decentralized, state-by-state nature of screening policies. “That’s how children fall through the cracks,” Tresa stresses.

Research priorities are also shifting. As individuals with UCDs begin to live longer, previously unconsidered issues are surfacing: how the conditions affect adults, how to support transitions from pediatric to adult care (especially with a lack of adult care providers for genetic and metabolic conditions, how protein-restricted diets may impact long-term health. Some patients who were stable for a decade are now showing symptoms that weren’t well understood a generation ago. New studies are exploring gene therapies and mRNA-based interventions that may one day offer a cure.

No matter what the future brings, the NUCDF will be there for your family. “Reach out; we are here to walk you through the UCD journey,” Tresa says. “The community will guide you.”

About the National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation

Our Mission: To save the lives and improve outcomes of individuals with urea cycle disorders.

Our Vision: A world where people with urea cycle disorders are rapidly diagnosed and effectively treated. Our dream is a CURE, and we can’t rest until we find it.

The National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation is the only nonprofit organization in the world solely dedicated to saving and improving the lives of children and adults from the catastrophic effects of urea cycle disorders. Formed in 1988 by a handful of parents whose children were affected, NUCDF has grown to be an internationally recognized leader in the fight to conquer urea cycle disorders (UCD) and raise awareness that saves lives. NUCDF is the driving force behind critical research to improve the understanding and management of UCD, find new treatments, and ultimately find a cure. NUCDF is a lifeline to UCD patients, families, and medical professionals worldwide seeking information, support, and HOPE.

Leave a comment