Jenny Jones can tell you exactly what she needs to know about every blood test, scan, and symptom she experiences. When her liver enzymes became elevated, she didn’t just ask her doctor why—she wanted a specific plan, liver monitoring, the thresholds for concern, and an understanding of which symptoms should warrant immediate action. Her doctor recently told her that she uses the patient portal more than anybody else, but to Jenny, that’s a good thing. For someone who spent years nervous about sharing her story of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and short bowel syndrome (SBS), Jenny’s transformation represents nothing short of a radical self-acceptance revolution.

“I didn’t have a lot of self-security with my diseases,” she tells me. Then, with a smile, she adds, “But I’ve come a long way.”

But Jenny’s journey to advocacy was not always smooth. In her interview with Rareatives, Jenny discusses the need for more mental health resources in the rare disease space, coping with grief and PTSD, and how she eventually learned to live with purpose through Life’s a Polyp.

The Path to Diagnosis

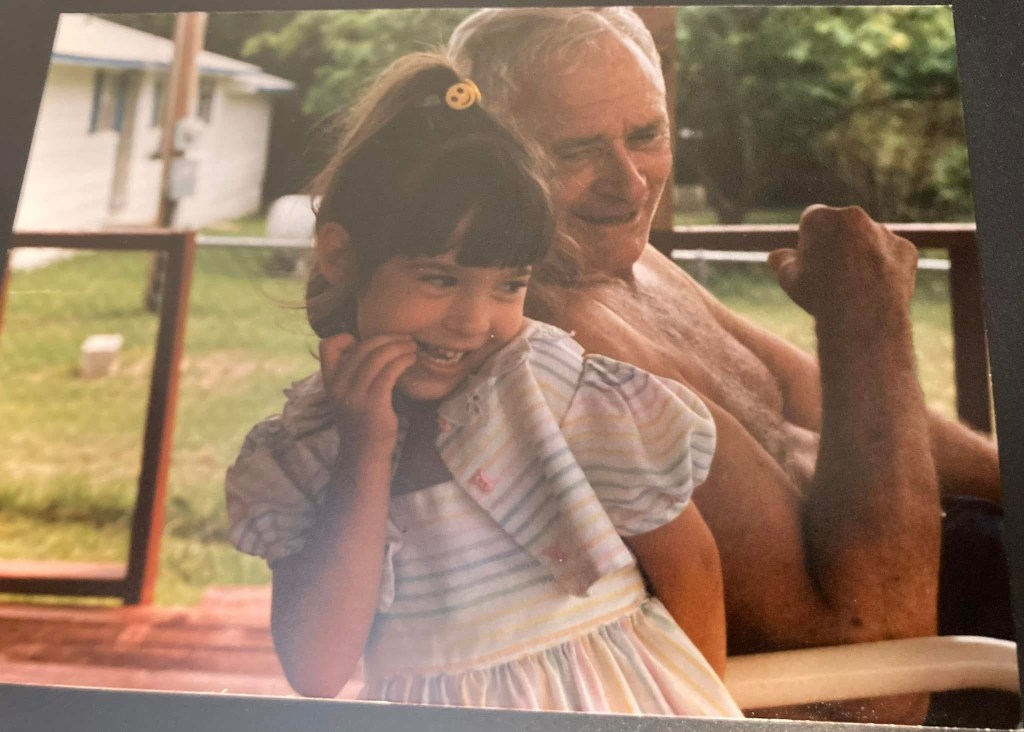

In the Jones household in the 1990s, familial adenomatous polyposis was a fact of daily life. Both Jenny’s grandfather and mother were diagnosed with FAP. Since FAP is an autosomal dominant condition—or a condition where only one mutated gene is needed for inheritance—Jenny had a 50% chance of inheriting the APC gene mutation that could cause hundreds, then thousands of colon polyps, predisposing her to colon cancer.

Back in the 1990s, our understanding of genetic conditions and management was completely different than today. Polyps were checked by a proctologist. And though genetic research was expanding at breakneck speeds, testing was in too-early stages to identify. “Today, if you or your partner has FAP, the child should have genetic testing at birth,” Jenny stresses.

But, after Jenny was born, the family waited in limbo. While they knew there was a chance Jenny would have FAP, there was no concrete way to be sure. Not until Jenny was older, or started showing symptoms.

The answer to the uncertainty came in chronic abdominal pain when Jenny was eight years old. Her pain was persistent, nagging. So her parents took her to a gastroenterologist. The doctor quickly determined that Jenny’s pain was caused by stress-related ulcers. Still, after hearing her family’s history, the doctor ordered testing. And, unbeknownst to Jenny and her family, the testing proved that Jenny did indeed have familial adenomatous polyposis.

What is Familial Adenomatous Polyposis?

Familial adenomatous polyposis is a rare inherited disease that predisposes individuals to colon cancer. People with FAP develop hundreds to thousands of precancerous polyps in the colon, which usually become cancerous between the 30s and 50s. “It’s always going to start in the colon and become cancer if not removed,” says Jenny.

But, as she’s quick to point out, “FAP contributes to so much more than colon cancer. There are also several other cancers people with FAP are at risk for.” According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), FAP also increases the risk of:

- Thyroid cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

- Central nervous system cancer

- Bile duct cancer

- Small intestine cancer

- Liver cancer

- Medulloblastoma

Additionally, some individuals with FAP also develop additional manifestations. These include dental abnormalities, bone growths, and soft tissue tumors like desmoid tumors which, though not considered cancerous, can cause significant damage within the body.

Medical Complications from Surgical Interventions

Surgery is the main treatment for FAP and may come in different forms. Typically, the entire colon is removed, though parts of the rectum may either be removed or preserved. According to 2014 research in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, individuals usually undergo surgery between ages 15-25. Jenny had a prophylactic colectomy, removing the colon before it could become cancerous, when she was just nine years old.

The plan, as surgeons explained it, was manageable. But the aftermath of the surgery proved anything but. “I had complications within the first few weeks, then a few after that,” Jenny explains. Within one year of her first procedure, Jenny had undergone five intensive surgeries in an attempt to address these complications.

These also led Jenny to develop short bowel syndrome. As she shares, “Short bowel syndrome is a malabsorption syndrome where the intestine does not function properly. Typically, it causes diarrhea, dehydration, and nutrient deficiencies. Some individuals require feeding tubes or a central line for Total Parenteral Nutrition.”

Throughout this process, starting after her first surgery, Jenny also found herself grappling with something entirely frightening: medical PTSD. And she’s not alone. According to research from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 33% of “traumatically-injured patients,” or those who underwent a serious and severe medical incident, developed PTSD. This can be extremely damaging for patients and their mental health. Work done by Dr. Nic Schmoyer-Edmiston, PhD, NCC found that medical PTSD can manifest in a variety of ways, including:

- Anxiety or depression

- Bursts of anger

- Hopelessness or helplessness

- Intrusive thoughts or memories

- Headaches

- Insomnia

- Fatigue

- Avoidance of medical procedures or settings

Worsening Medical PTSD

As she grew older, and through middle school, managing her condition was fairly straightforward. Jenny was underweight, so physicians were constantly trying to determine how to get her to a healthier weight. She also had to take iron supplements.

As a note, people with FAP commonly develop iron deficient anemia and require supplementation. However, iron may accelerate tumor growth in colorectal cancer, so individuals with FAP that progressed to colorectal cancer should not use any iron supplementation without speaking to their doctors.

But, when Jenny hit high school, she was ready for a change: specifically, an ostomy reversal. “I was only supposed to have my ostomy for about three months,” she explains, “but by that point, I had had it for six years.”

Ostomy reversals can come with potential side effects, some which might be debilitating to quality of life: bowel dysregulation, gassiness and bloating, abdominal pain. But Jenny was confident that she could handle these issues and get past them.

Unfortunately, the surgery did not go as planned. Her short bowel syndrome contributed to the development of further complications, including intestinal strictures. It took another five years and multiple surgeries for Jenny’s condition to stabilize and, throughout this process, her medical PTSD was heavily exacerbated.

In Jenny’s case, the delayed healing was only part of the trauma. She had also lost trust in her body, in medicine, and in those making decisions around her care. Recovery was difficult, and coping didn’t quite come naturally.

Her father also shared something which compounded this trauma. As Jenny shares, “Apparently the first surgeon was actually pushing for an ostomy and not a reversal.” She pauses, then carefully adds, “I’m not saying they intentionally did anything, but it does make you wonder.”

As she reflects, Jenny describes how the medical system could improve for patients, surmising that more counseling and mental health resources could reduce the risk of PTSD development. “Having a rare disease affects so much,” she says. “We would have really benefited from individual and family counseling. I’d love to see an integration of social work into healthcare clinics, or at least a greater partnership between hospitals, doctors, and local mental health providers.”

Life’s a Polyp

As a way to help cope with her surgical complications, and to unpack what living with FAP and SBS meant for her, Jenny began a blog entitled Life’s a Polyp. It became a significant emotional outlet, a place where she could process trauma or write things that she wasn’t yet comfortable saying out loud. In fact, the website was even anonymous initially—not even an email address.

At the same time, Jenny also began counseling, which strengthened her self-assurance. Writing more about her experiences, she says, “also taught me self-love and acceptance.”

Then, one day, an email arrived in her inbox from a woman aligned with Michael’s Mission, a nonprofit organization designed to improve treatment options and quality-of-life for individuals with colorectal cancer. The woman’s message was simple: consider using your real name. Let people see you.

“She did a bunch of research to contact me, and she really encouraged me to share who I was,” Jenny says. At first, the prospect unnerved her. Putting her name on Life’s a Polyp meant owning her story publicly and being vulnerable on a scale she hadn’t previously allowed herself.

But something about that encouragement, combined with the growing support she was finding in FAP Facebook groups and the connections she was making with other patients, gave her the courage to take that step.

“When I did, it allowed me to grow into this space where I can start to embody self-love,” she reflects. “I’m still working on self-worth, but I’m so glad I was empowered through these various factors that helped me learn it’s okay to be who I am and okay if people know about my conditions. Now I’m an open book. Life’s a Polyp has been so transformational for me.”

Building What She Needed

Today, Life’s a Polyp is far more than a blog. Jenny has expanded her reach through a comprehensive platform that includes informative Youtube videos, social media accounts, and podcast appearances. “There are so many places to connect with others and share resources, information, and education,” she says.

But more importantly, Jenny is building an infrastructure of support. She established the FAP Research Fund with NORD, with her online shop helping to fund research. She also wrote a children’s book about FAP entitled Life’s a Polyp: with Zeke and Katie, a resource she wishes had existed when she was diagnosed.

“I didn’t want people to go through the same things I did physically and mentally,” she shares. “While there’s an online FAP & Me guide for kids which simplifies the information, I thought what if I could make it more fun to learn about? What if I could open the door to discussing cancer, ostomies, mental health, resources for children and adults, and most of all, how we all get through this together?”

Her newest project, launching this September, might be her most personal: a podcast with her cousin about grief after they both lost their mothers. The podcast will not only share their mothers’ stories, but will explore the grief journey. All funds from a t-shirt campaign around the podcast’s launch will be split between FAP research and Alzheimer’s research, in honor of the disease Jenny’s aunt passed from.

The Future She’s Fighting For

Moving forward, Jenny wants to make a change, on both macro and micro levels. From a big picture view, Jenny hopes to change FAP treatment and research through funding and awareness. She believes gene editing could be a useful tool.

“Ideally, I’d love to get to a point where instead of delaying surgery, we can prevent it altogether, and gene editing is going to be the best option,” she says. “If scientists could just turn on the tumor suppressor gene that is turned off in FAP, we could address this at the source.”

Jenny encourages every person with a rare disease to advocate for themselves. She says, “Educate yourself on your disease as much as you can, and advocate for yourself. Research on your own. Read the medical journals and studies. Connect with the community. But also ask questions. Be persistent. Take everything you read to your doctors. Look and analyze your tests. And don’t let up.”

On a more personal level, Jenny wants people to recognize not only that they’re not alone, but that they can also be their own biggest advocates. When she thinks back to her childhood, she remembers how she closed people out, afraid to get hurt.

“Looking back, I’d tell my younger self that I wasn’t alone. I just needed to talk to someone. If you’re not letting people in, it is extremely damaging and hurtful to yourself,” she reinforces.

Because Jenny discovered what every rare disease advocate eventually learns: your story, shared openly, becomes medicine for others walking the same path. And sometimes, in the sharing, it becomes medicine for yourself too.

For more information about FAP, or to follow along on Jenny’s journey, visit Life’s a Polyp and follow her upcoming podcast about grief and inherited illness. You can also find Life’s a Polyp on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and TikTok.

Leave a comment